“Just as the world was beginning to recover from the disruption of Covid‑19, global cities encountered a new wave of challenges from high inflation and slowing growth to an energy crisis and increasing threat of climate change”. Such a complicated context makes the premises for the Urban Mobility Readiness Index 2022, by the Oliver Wyman Forum and the University of California, Berkeley, ranking 60 global cities on how prepared they are for mobility’s next chapter.

By conducting research and collaborations with leaders from the public and private sectors, the Oliver Wyman Forum helps organizations confront the most-pressing societal challenges and foster growth and opportunity, in different sectors (climate & sustainability, future of money, global consumer sentiment, markets, mobility), and even nowadays, when “technology is disrupting industries at a faster pace than ever while business faces growing demands to address social issues, climate change, and geopolitical crises”.

The Index is the result of research realized by a team of experts, academics, business leaders, industry advisors and consultants in mobility. After showing the achievements from the most prominent cities in sustainability and innovation in mobility, according to the report, Infra The Mundys Journal has reached out to Guillaume Thibault, Partner and Mobility Co-lead, the Oliver Wyman Forum. In partnership with Alexander Bayen, Associate Provost, UC Berkeley, Mr. Thibault launched the annual Oliver Wyman Forum Urban Mobility Readiness Index in 2019 and continues to oversee its implementation today.

Mr. Thibault, what are the biggest problems for public transit agencies today, after the pandemic and while energy costs are increasing?

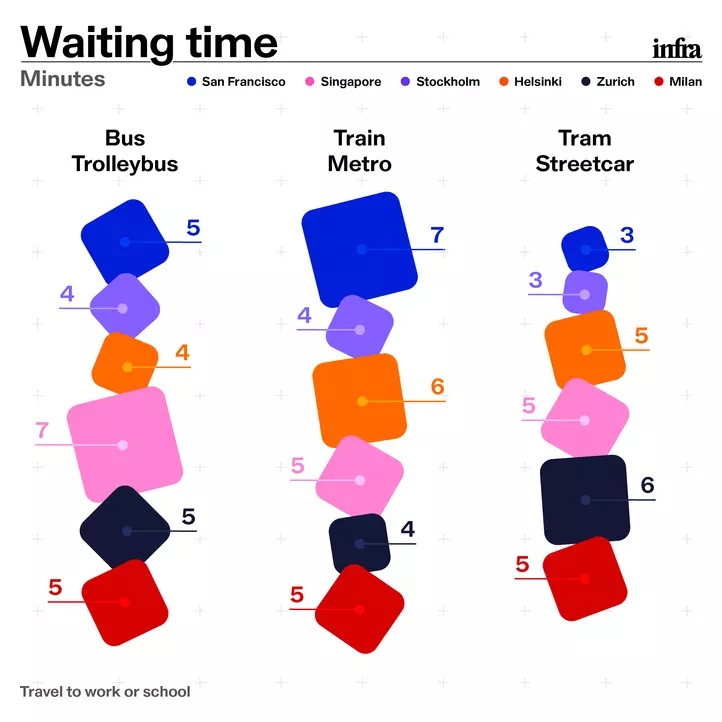

“The pandemic has profoundly changed mobility patterns, with remote working here to stay. As a consequence, public transit agencies have observed a drop in commuters’ public transit demand and associated reduced revenue. Bringing commuters back is the main priority and they need to maintain or improve the level of service if they do not want to lose more riders. However, with increased operating costs and labour shortages, alongside financial challenges, many services have been reduced and wait times have increased. This is even more relevant in the current context of increasing energy prices, which have strained budgets of transit agencies, further impacting on service maintenance and infrastructure investments. And passengers are not willing to, or are unable to, pay more for their commutes.

Nevertheless, we do see improvements. Data collected via our Global Consumer Sentiment Survey (across 10 countries) has shown that public transit usage has been steadily recovering over the past 18 months. Although demand remains below pre-pandemic levels, the trend is moving in the right direction for transit agencies, despite these complex challenges they are facing”.

What are the key levers to bring commuters back to public transit?

“Our latest Global Consumer Sentiment survey shows that affordability is the primary concern for travelers when selecting transportation mode. The price of public transit fares play a critical role in encouraging commuters back to public transit. Agencies can consider reducing or freezing fares, or providing subsidies or financial incentives – pertinent with the current cost-of-living crisis. Similar initiatives in Spain and Germany last year have proved to be successful experiments in boosting ridership.

Commuters have also become more demanding when it comes to availability and accessibility of public transit services. Investing in the mobility offering translates into higher public transit utilization. A good example of this is Hong Kong, thanks to high station density, reliable service, and affordable fares.

Another important factor is personal safety, which has increased in importance over the last year, and it is still an important consideration from public transit agencies. They need to tackle this problem if they want to increase ridership and cities like New York have announced plans to address rising criminality”.

Is car sharing really functional in reducing private transportation or is it just a comfortable and subsidiary alternative to public transportation? Is it recovering, after the pandemic shock?

“Car sharing does have a role to play in reducing private transportation with studies pointing to one car having the potential to replace up to 20 private vehicles. The potential impact is real. Yet lowering car ownership will require to bring car sharing to scale. Today, there are not enough vehicles and users to make car sharing an attractive alternative to owning a car and greater than 75% of consumers in our Global Consumer Sentiment survey have not used car sharing services in the past year. Our Value Pool analysis forecasted that the car-sharing market would grow to reach ~$24 bn by 2030 (compared to $7 bn in 2020). Although the pandemic had an impact on the industry, the market will continue its expansion. Additionally, the effectiveness of car sharing in reducing private transportation may also depend on cultural and social factors, as well as government policies and incentives to increase utilization”.

Will the transition to EVs make the number of private cars decrease?

“The impact of EVs and the shift to sustainable mobility on the number of private cars will be dependent on several factors. On one hand, government policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions – such as low-emission zones, bans on sales of Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles etc. – may reduce the number of private cars due to affordability constraints. Not only because of electric engines but also owing to connectivity and automated features. The price of EVs relative to ICE vehicles is one of the main barriers for potential buyers, as outlined in our Global Consumer Sentiment Survey. As such, in the short-term, one can anticipate private cars use may decrease as a large share of the population cannot afford them.

But things may change fast. Price parity between electric and combustion engines is expected in 2026. More importantly, the used car market is starting to take-off bringing EVs to middle- and lower-income populations. It will be a game changer in the next few years.

On the other hand, the environmental impact and lower fuel costs associated with EVs may contribute to their popularity. And, as technology advances – with longer range and faster charging – as well as improved charging infrastructure, EVs become a more viable and appealing option for consumers.

The other parameter that might play a larger role in car ownership is city restrictions. Car-free zones, parking restrictions and other incentives to turn travellers towards other modes have been implemented by several cities. It is yet to be seen whether all cities will follow suit”.

Is the Road Usage Charge (RUC) a doable model for any city and a proper lever to finance public transit?

“The RUC has been successfully implemented across some countries and states – such as Oregon in the US, and New Zealand – as a way to overcome funding issues as more electric and fuel-efficient vehicles enter the market. However, this may not be a feasible option for all cities and regions. Implementation requires significant infrastructure and technology investments to track and collect payments related to distance travelled, and there may be resistance from drivers from an economic and privacy perspective. Resistance from drivers, may actually incentivize residents to travel by car less and shift to other modes of transportation – increasing public transit usage. Although the RUC may provide a promising model to finance transportation services, public transit agencies need to explore more funding sources to ensure financial sustainability to meet the transportation needs of their commuters”.

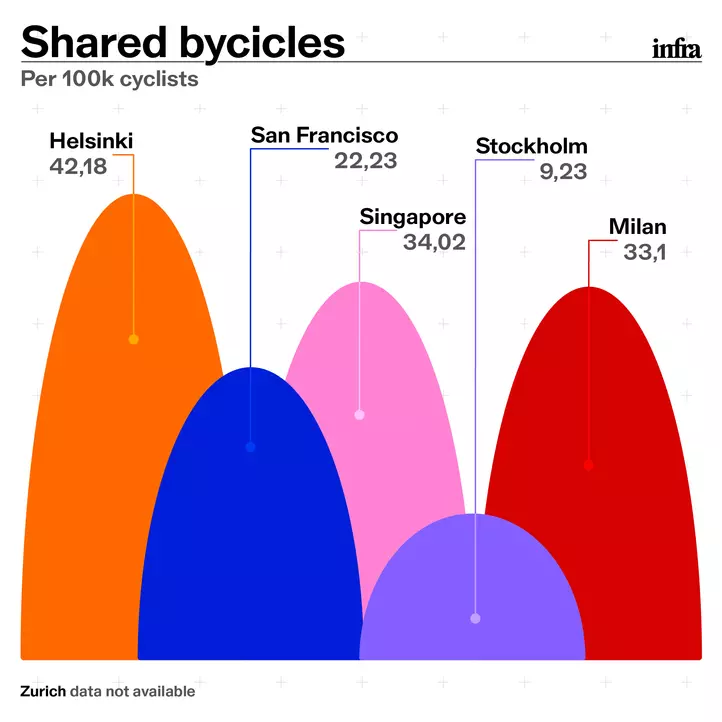

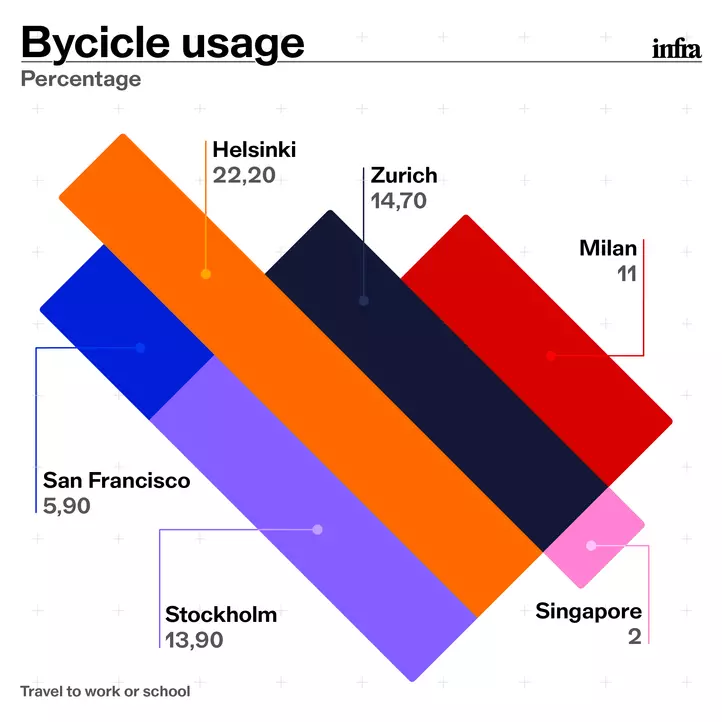

Is the future of urban mobility active (cycling, kick scooter, walking...) or automated? Will AVs increase road congestion, given its comfortable "driving" experience?

“It will be both active and automated. There is no silver bullet. Urban mobility must be more efficient to address future needs, in particular, in the rising urbanization context. It means that cities need to optimize road space. Promoting active mobility is an excellent way forward. At the same time, vehicles will remain a central part of urban mobility but it will require a different approach. Automated vehicles appear as a good solution to make the fleet more efficient while reducing car ownership. It even has the potential to make mobility more affordable and accessible. The mobility use case for automated vehicles will be an important parameter for road congestion. We also need to clarify the level of automation that will be rolled out. It is likely that in 2030 most new vehicles will have automated features but fewer vehicles will be fully automated (level 5). If one wants people to give up their personal vehicle and lower congestion, a reliable fleet of automated shared vehicles will be needed with sufficient density.

However, active mobility will happen sooner than automated mobility. Technical and regulatory challenges still need to be tackled before seeing large-scale deployment”.