“The first measure if I were to be a councillor in Milan again? Putting a price on Area B, to make it a mechanism that objectively reduces access to the city”. This is answered by Edoardo Croci, professor of Transport and Climate Change and Sustainable Urban Regeneration at Bocconi University, former appointee of the Moratti council, for Mobility and Environment, from 2006 to 2009. Today, 'the most European of Italian cities' is 31st out of 60 cities in the world, according to the Urban Mobility Readiness Index (see more data in photogallery, En) and in the eyes of a part of public opinion has lost attractiveness in the post-Covid. On transport, traffic quality and pollution, we spoke with Croci (in the picture below, En), proponent of Ecopass, the first pollution charge in Milan's history, followed by BikeMi, the first bike sharing, also in 2008.

Professor, how has Milan changed since then?

“Road pricing was a turning point followed by other sustainable mobility measures that improved traffic and air quality. Pollution is not a solved problem, of course, but the coherence of administrations and the favour of citizens have made it so that no one asks for a change of direction. Today the motorisation rate has dropped by 10 per cent, there is a wide variety of mobility options and everyone uses apps to calculate the best route and mode.”

What does that experience teach us in the aftermath of Area B?

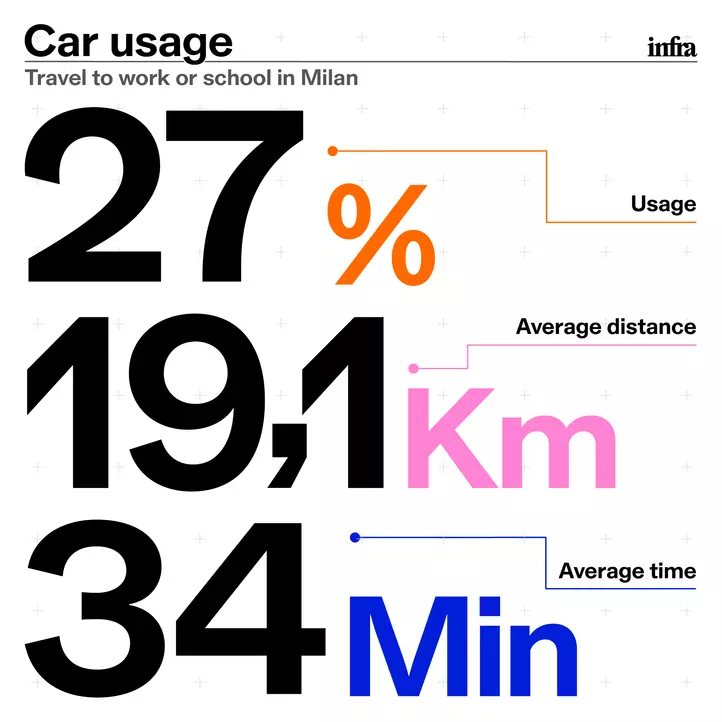

“That one must make even seemingly unpopular decisions if they are justified by analyses and impact studies and not be afraid to adopt an instrument based on price. Today, two-thirds of internal trips in Milan are by public or sustainable transport, but hinterland-city trips see 900,000 private car journeys per day, with an inverse modal proportion. It must be decided that Area B can be subject to road pricing, perhaps with a lower ratio and different rules from Area C (the congestion charge heir to Ecopass, ed). Compared to a purely regulatory policy based on vehicle standards, with immediate effects but potentially higher social costs, pricing can be more flexible. The challenge must be met with the development of the metro, railways and extending the buses, shuttles and first-mile car sharing services, to enable hinterland residents to reach stations without using their cars. And imagine preferential formulas for car sharing and carpooling.”

How to make public transport attractive again, in the post-Covid era?

“Unfortunately, one also gets used to bad habits and once the emergency was over, commuters have not returned to using local public transport (LPT), down 20% compared to pre-Covid. It is not enough that car accesses in Area B fell by 4.3% compared to a year ago, in the first three months: the comparison must be made with the pre-pandemic period. If one factor is the increase in ticket costs, the cost of road pricing must also be increased in order to rebalance and restore competitiveness to the LPT. The metro line 4 will have a major effect and there are the new modes of transport. Investments take a long time, we have to move forward together on all fronts.”

There will be a need for parking spaces, but for many motorists it is just a cash grab...

“Interchange parking spaces were properly made near the termini as the metro was developed. The extra step, which no administration has ever had the courage to take, is to make residents pay for parking too, perhaps with a subsidised form of season ticket. Parking a car is a private interest and owning one is not mandatory. It is time to make everyone realise that urban space is a limited resource and those who use it for parking have no right to it but must pay for it. It is a fact of social justice that applies to residents and non-residents alike.”

Don't measures such as these make Milan less attractive, less affordable, creating a centre of the 'privileged'?

“That's not the point, the opposite is true. These measures do not reduce access to the city or trade, there has only been a modal shift: fewer cars, more metro. It is a matter of fairness and social cost: these measures are taken to improve poor air quality, the effects of which mainly affect the weaker sections of the population. The historic centre on the other hand multiplies its population tenfold during daylight hours and action must be taken to improve it, because it belongs to everyone. The large investments in urban regeneration that have taken place in many neighbourhoods in recent years in Milan make it difficult to say that there is a single centre and this, together with a demand for housing that is higher than the supply, has caused property prices to rise. Milan has high costs but offers an incomparably better LPT service than the rest of Italy and at a lower cost than other European metropolises. The quality of LPT is an element of attractiveness, because it allows people to get around without using a car and everyone considers this factor, along with the cost of housing, the quality of public services and green areas. Finally, Milan is small and flat, you can get around very well on foot or by bike, although alas it is still difficult.”

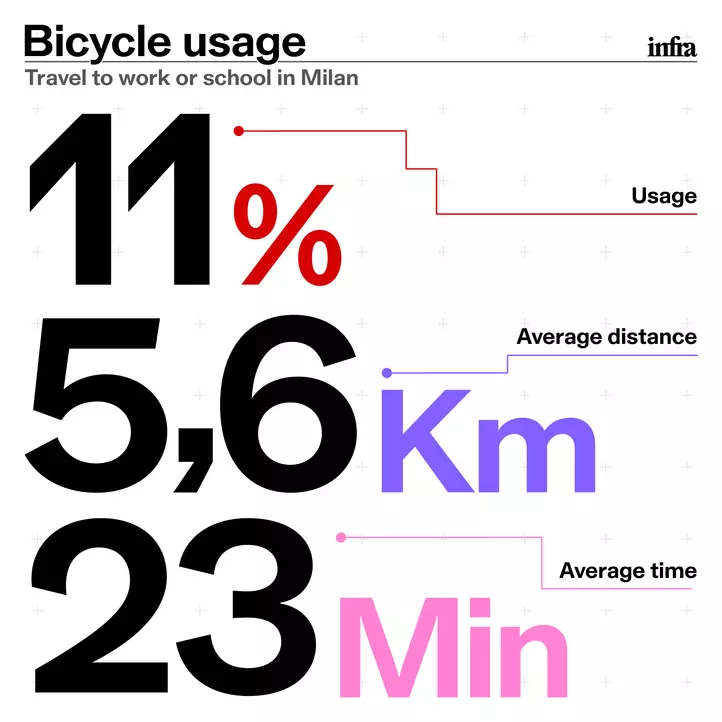

Why is it that cycle lanes continue to be created but accidents cannot be avoided?

“The network has grown but is not yet integrated, so that journeys can be made in protected lanes. We have bits of 'light' bike lanes, a painted strip next to the pavement, the car lane and parked cars. This is the case on Corso Buenos Aires where parking should be removed, and the cycle path separated with a kerb. The number of cars should not be seen as a constant, if you invest in sustainable mobility the number of cars decreases and thus also the demand for parking. We need the courage to make choices that are unpopular but rewarding in the medium term.”

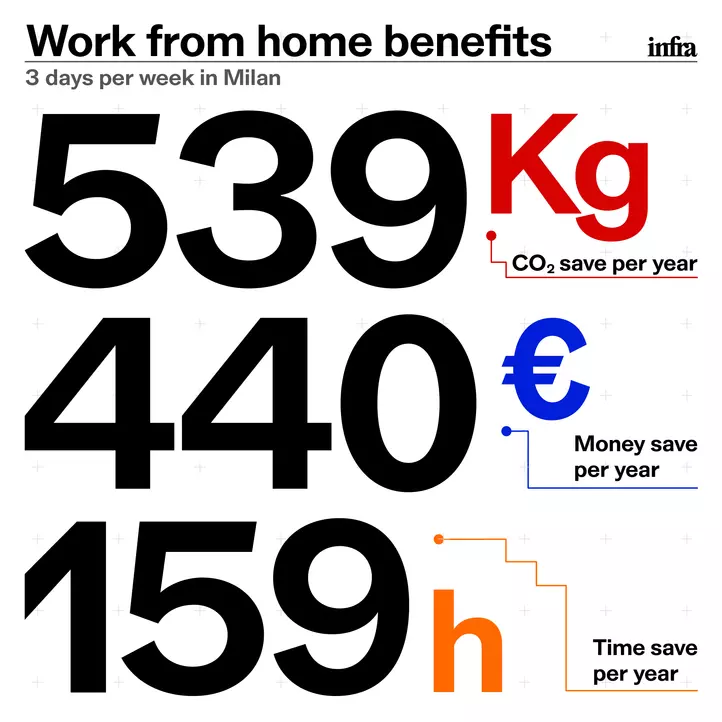

Policies oriented towards sustainable mobility are often interpreted as a deprivation of freedom of movement. How is a change of mentality from car ownership to mobility as a service possible?

“Freedom of choice on how to move is fundamental, but different behaviour corresponds to different costs, a different public favour or disincentive. There is a growing realisation that there is no need to own a car that sits idle for 95 per cent of the time, but that alternative mobility is needed, to be evaluated on the basis of cost and convenience. Car manufacturers themselves are increasingly aware that car ownership is decreasing in urban areas and that sharing services will increasingly play their role in the market.”