One of the effects of the war in Ukraine has been adding new political significance to the reasons why the European Union is committed to gradually giving up fossil fuels as a source of energy. The two steps envisaged by the EU are the “Fit-for-55” programme for cutting emissions 55% by the year 2030, and the Green Deal, the cornerstone of which is achievement of zero emissions by 2050. Europe’s goals were - and are - climate-related, leading the global process of decarbonisation to comply with the limits set by the Paris Agreement and encourage the most reluctant nations (India, China, Russia) to do the same.

But there is now a new key to the contrast between these two forms of energy, fossil and renewable. Sun and wind are “local” products that may vary with the weather, but are not affected by geopolitical developments. Oil and gas are “international” products purchased on turbulent markets from partners who behave in unforeseeable ways, producing dysfunctional relationships. They represent a danger zone and a strategic vulnerability.

The European Union found itself in an uncomfortable position when the war broke out: 40% of the natural gas consumed in Europe comes from Russia, an essential form of trade with the invader that Europe is unable to give up in the near future. European nations now have to face the results of all the time wasted without making progress on the energy transition, especially the most exposed countries, such as Italy, where gas still plays a major role in the generation of electricity and progress on renewables has been delayed by decades, and Germany, which had been working on doubling its gas pipeline from Russia, Nord Stream 2, only to halt it in the final phase, authorisation, because of the war. Nord Stream 2 could well be the first in a series of stranded assets left behind by this war. And so, in addition to its two long-term plans, Fit for 55 and the Green Deal, the EU has had to add a tough short-term goal: cutting its dependency on Russian gas by 80% before the end of the year. The decision could turn out to be problematic: this energy crisis could either speed up the energy transition or bog it down, and the signals so far suggest it could go either way.

A new relationship with energy

The good news is that, as in the 1973 oil crisis, war has revived debate about the big missing piece in our decarbonisation strategies: saving energy and improving energy efficiency. If implemented with the right strategy, this policy does not mean austerity, nor lower quality of life; it means a more advanced, adult attitude to energy. It’s a two-way street: human behaviour and technological innovation.

Think tank Ecco has calculated that just setting the thermostat one degree lower in our homes and offices would allow us to consume 7% less gas as a nation. A large-scale campaign providing information on how to save energy could save another 10%. Turning off lights when not required and putting on an extra layer instead of wearing short sleeves at home in winter could make it unnecessary for our nation to purchase a total of 7 billion cubic metres of gas a year. Another piece in the puzzle is thermal conversion of buildings: replacing gas-fired boilers with heat pumps in just 10% of buildings would save another billion cubic metres of gas. All it would take would be an adjustment to Italy’s existing “Superbonus 110” tax deduction plan, which currently provides tax incentives even if natural gas-fired boilers are maintained. According to Bloomberg, the current energy crisis could also lead to setting of even more ambitious targets for renewables and energy efficiency to be reached by 2030.

Europe is at a crossroads

The other side of the coin is social and political panic about energy and raw materials costs and the fear that supplies could be suddenly cut off. This wartime economy mentality has driven Italy to consider the possibility of slowing down the phasing out of coal as an energy source (scheduled for 2025, though the country is ahead of the deadline so far) or even use of fuel oil, a resource used in Post-war times (though at this point we may well ask “which” post-war?). Germany faces the same dilemma, implementing ambitious plans for development of renewable resources while at the same time risking a delay in the phasing out of coal (its central, prevalent energy source). The Vice President of the European Commission and “EU climate man” Franz Timmermans said it himself in the second week of the conflict: “In this situation, coal must not be taboo”. In only a few months the Union has dismantled the position it firmly held at COP-26 in Glasgow in November: “Consigning coal to history”.

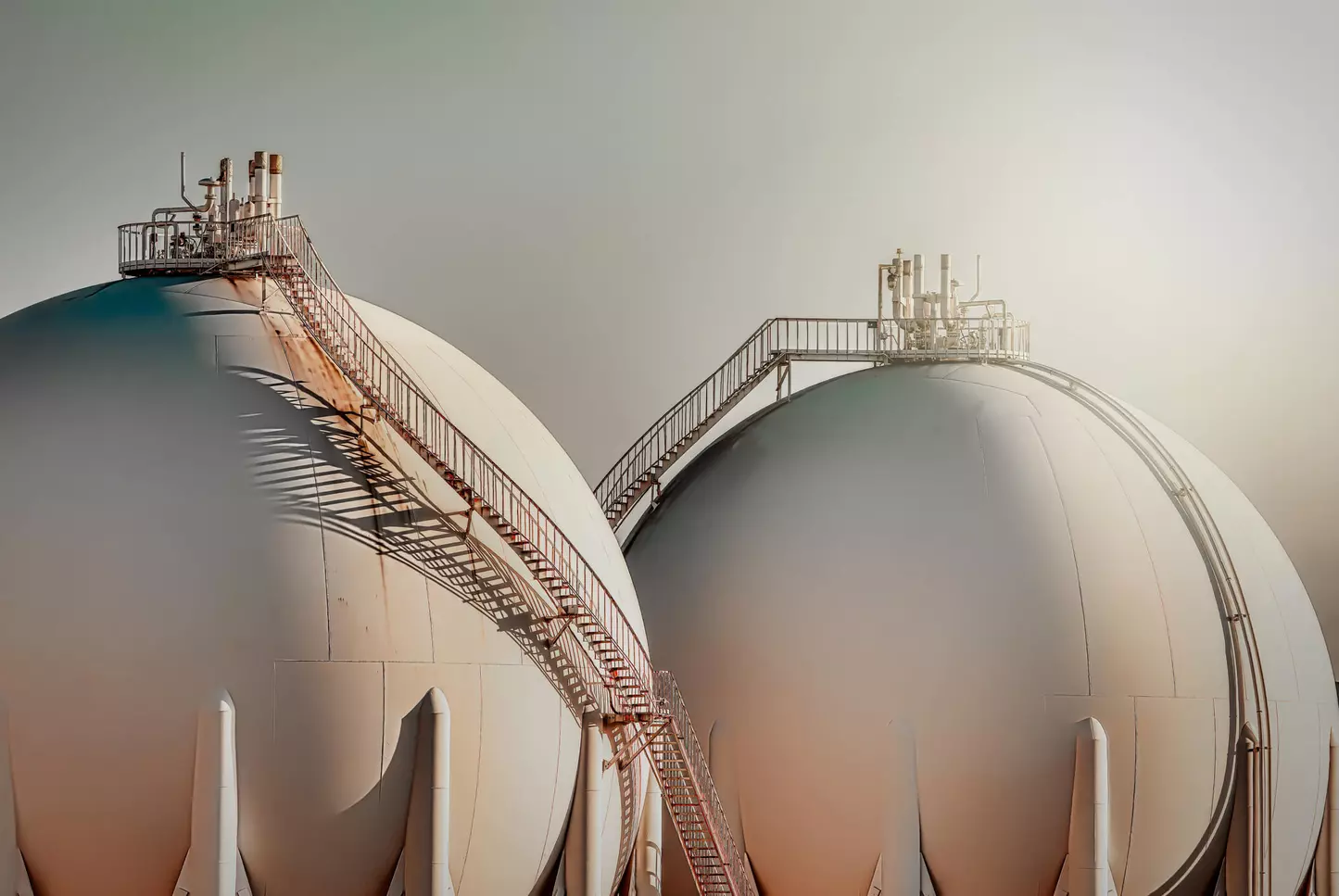

But now history is getting its own back, and the EU finds itself at a crossroads, faced with a choice between fossil fuels and clean energy. This is confirmed by another piece in the puzzle of the strategy for reducing dependency on Russian gas: a strong focus on LNG (Liquid natural gas), which travels by sea and must be regassified before it enters the system. Just under half of the 112 billion cubic metres of Russian gas that Europe needs to replace in the short term (50 billion m3) will be replaced by liquefied natural gas, coming primarily from the United States. The problem is that this requires new infrastructure, which risks becoming yet another stranded asset or continuing our dependence on gas beyond the deadlines set by Europe’s climate targets. A case study for understanding this paradox is a new infrastructure planned in Germany, an 8 billion cubic metre terminal in Brunsbüttel, on the banks of the Elbe River. It will take about three years to build. The terminal will be ready in 2025, but Germany has promised to phase out use of natural gas entirely only ten years later, in 2035.

Technologies, resources and supply chains

The last piece of the puzzle is industrial: to speed up the energy transition, the European Union needs a production policy consistent with its ambitions. Today, only two out of every hundred photovoltaic panels in the world are made in Europe, and seven of the ten biggest factories are in China. In 2021, according to the European Commission, 25% of Europe’s plans for installation of photovoltaic panels were postponed or cancelled due to lack of materials. To electrify the system and stop using fossil fuels, the European Union must play a more central role in the supply chain for critical metals. The resources are there, under the ground, but protests against mining of lithium and rare earths in Spain, Portugal, Greenland and Serbia demonstrate that Europe will not become a mining continent again and the only alternative is recycling and the circular economy.

Far away from the war, but pertaining to the same general topic, tense discussion is currently underway in the European Commission about another key issue, continent-wide regulations governing batteries, essential for electric cars and accumulators of renewable energy. To achieve independence from complicated global markets for lithium, cobalt and nickel and prevent the emergence of new dependencies, the Commission proposes high levels of recycling of materials from exhausted batteries. If this measure passes, the European standard will have a positive impact not only on use of resources, but on a key factor whose importance has become evident in recent weeks: independence.