“Since 2006, road fatalities have fallen from 365 to 108 each year in Ireland and from 154 to 136 each hour worldwide, but road accidents remained the leading cause of death for young people aged 5 to 29. Losing a child so suddenly and violently should be preventable for millions of parents around the world. Lives are much more than a number.”

This is the painful testimony of Donna Price, at the presentation of the Global status report on road safety 2023, the World Health Organisation's five-year study on the results of the Decade of Action for Road Safety. Nevertheless, since losing her son, Price has found the energy to set up and lead the Irish Road Victims Association, which is active on this front.

However cold, numbers remain a metric necessity if the shared goal is to raise consciences and inspire society and individuals to act to prevent these deaths. The Global status report collects statistics on road deaths in countries around the world to serve one purpose: to reduce the number of fatalities globally by 50% every decade.

The 2023 report (fifth edition) is based on data from 2021 and details the situation in Europe, the Americas, the East Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, the West Pacific and Africa. A few messages remain on the ground, once the key numbers are highlighted:

- road traffic fatalities were 1.19 million in 2021 (-5% since 2010), approximately 3,200 per day and 2 per minute;

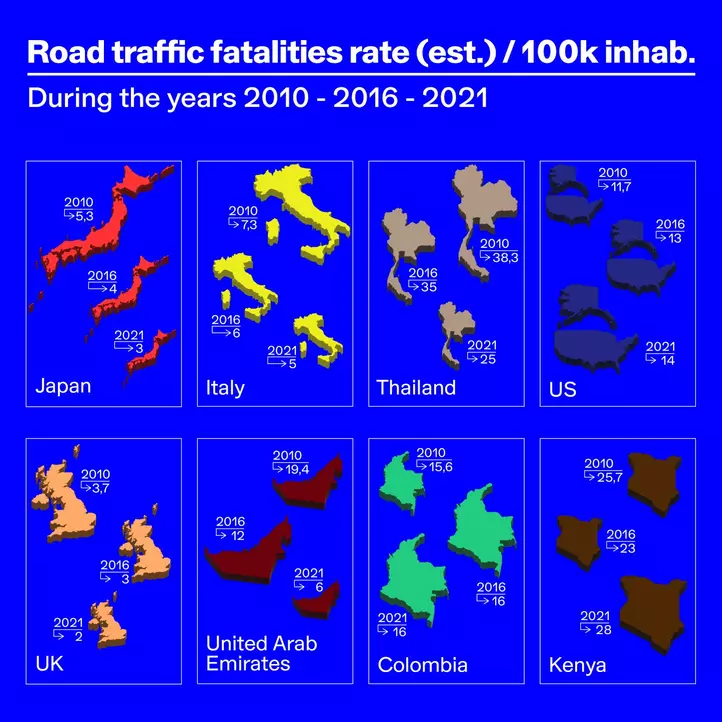

- the mortality rate remains 15 per 100,000 people. Considering the one billion increase in population (+13%), there was a decrease of -16%;

- only 10 countries have halved the number of deaths: Belarus, Brunei, Denmark, Japan (see infographic, Author’s note), Lithuania, Norway, Russia, Trinidad & Tobago, United Arab Emirates (see infographic), Venezuela.

Inequalities persist

“The burden of road deaths costs $1.8 trillion a year, 10-12% of global GDP: what could we do using all this money in a different way, for the benefit of road users?” asks Jean Todt, UN Special Envoy for Road Safety.

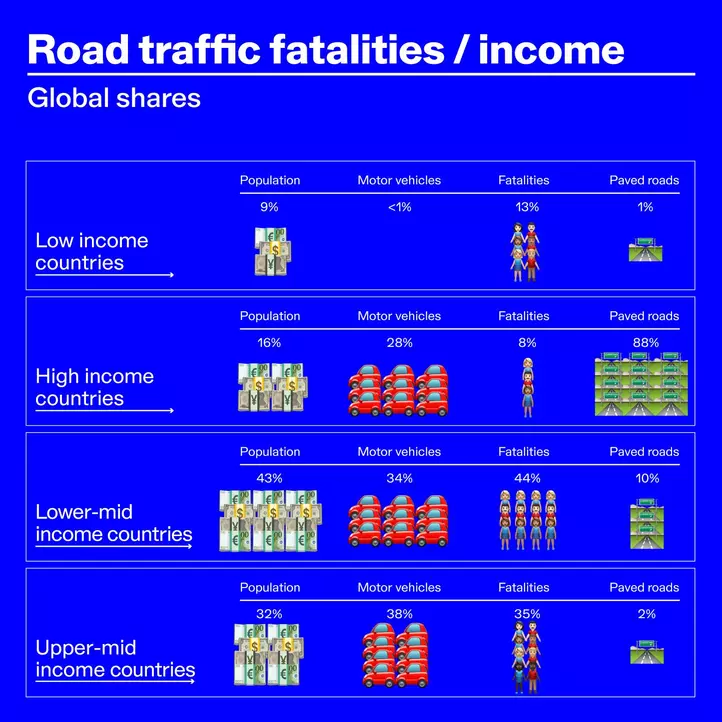

The economic aspect of the issue becomes even more apparent when we observe that 92% of all deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. Two out of three are of working age (18-59).

Immense losses for families in the poorest countries where 9 per cent of the global population lives, owning less than 1% of the world's motor vehicles, just 1% of the world's paved roads, but where, with obvious disproportion, 13% of road deaths occur.

In contrast, high-income countries have 88% of the world's paved roads and one in four motor vehicles (28%), but they account for 8% of the victims. The WHO summarises that the world's poor are three times more likely to die from a road accident than the richest.

Africa, for example, has the worst mortality rate (19 per 100,000) and the number of deaths is even increasing (+17%), while Europe has the lowest mortality rate (7 per 100,000) and the steepest decline in deaths (-36%). Almost one out of every two countries (28 out of 66) with the number of victims increasing is African.

A new model of mobility

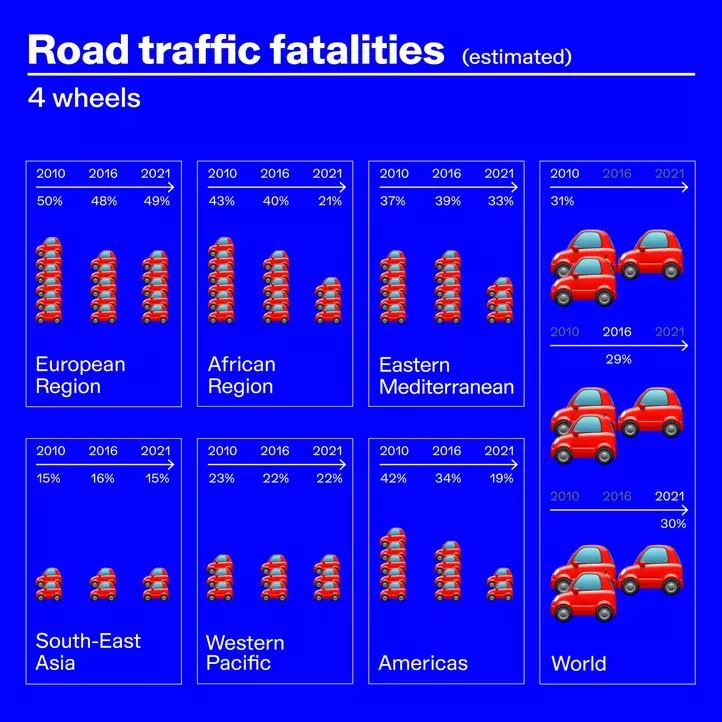

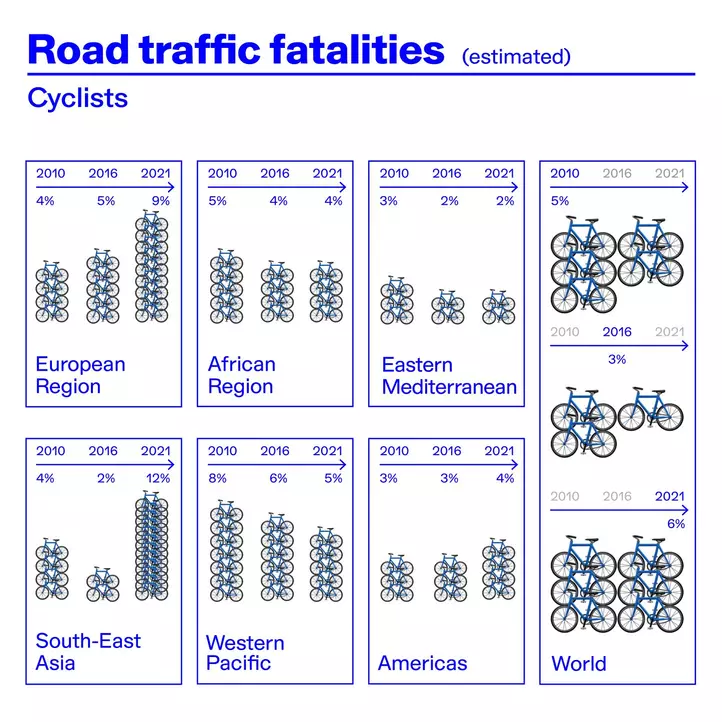

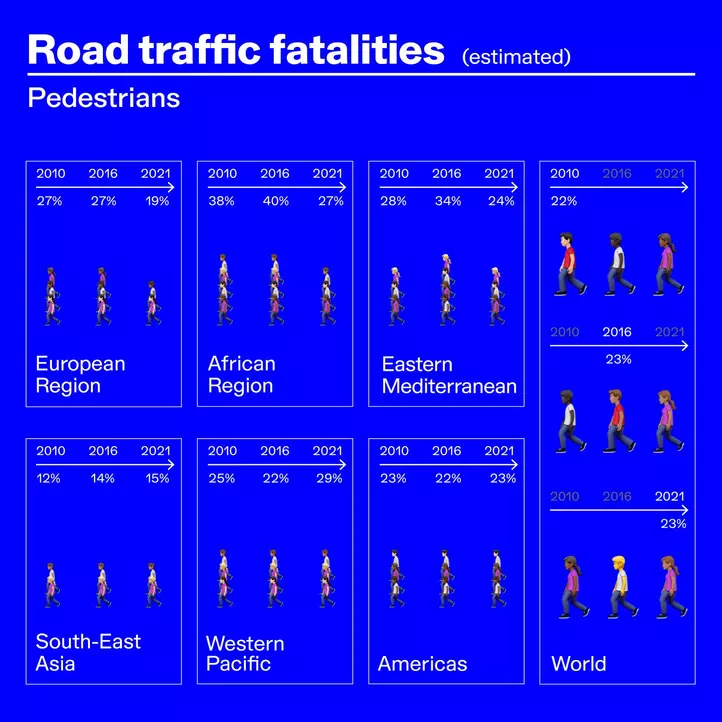

Most people describe themselves firstly as pedestrians or public transport users and only thirdly as motorists. Nevertheless, more than half of the victims are soft or light mobility users. Pedestrians and cyclists account for 23% and 6% of the victims, the most disadvantaged section of the population in many countries.

Nevertheless, 85% of the world's transport vehicles are four-wheelers and the global fleet of motor vehicles has more than doubled (+160%). Yet, the mobility model based on private ownership of vehicles will increasingly show its limits, especially in cities, where 60 per cent of the population will live in 2030. A paradigm shift becomes necessary.

“We call on all countries to put people instead of cars at the centre of their transport systems, for a safe, efficient and sustainable mix that includes mass public transport, improving the safety of pedestrians, cyclists and other vulnerable users. Safe mobility is a crucial aspect of the universal right to health and should not be achieved at the tragic cost in human lives. We know what works, political will must meet the scale and urgency of the crisis.”

Roads suitable for all

The appeal by Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the WHO, seems all the more centred considering that the majority of roads continue to be built for a growing fleet of motor vehicles. Well, while 40% have a satisfactory quality for four-wheelers, 80% do not even meet basic standards for pedestrians and cycle paths are only 0.2% of the length.

The complexity of technological innovation adds to this scenario. For example, in Southeast Asia and Europe, cyclist fatalities increased by 200 and 125%, globally by 20%: “Data from some countries suggest that this increase is due in part to the electrification of bicycles, which has led to an increase in cycling, especially among vulnerable elderly, in cities often lacking adequate cycling infrastructure,” the report states.

Nevertheless, only 51 countries legally require safety checks to ensure all road users are safe. And, according to the World Bank, more than USD 800 billion is spent each year on infrastructure development by public and private investors, ranging from less than 1% to 5% of the GDP of individual countries between 2019 and 2021.

Between laws and political will

If road fatalities are an ‘undeclared pandemic’, as they are often called, “road education, laws, infrastructure, post-accident service are the vaccine and we must use it,” says Todt, who lists good rules for drivers and passengers: use of helmets, observance of speed limits, no drinking, using drugs or texting while driving, use of seat belts, child protection.

But the global status report highlights serious regulatory deficiencies, everywhere in the world:

- only 6 countries have laws defining all 5 of these good standards

- only 16 adhere to all 7 UN conventions on road traffic, road signs, periodic inspections, component requirements, international transport workers and the transport of dangerous goods

- only 35 have legislation on safety features for car equipment

- only 16 national road safety strategies are actually funded, out of 117 declared

A further dimension links international policies, national laws, private business and social inequalities, for example in the market for new vehicles, since ‘where standards legislation is weak, manufacturers can ‘despecify’ life-saving technologies in new models sold in countries where regulations are weak or non-existent, to reduce costs.”

As for used vehicles, two out of three vehicles exported (66% of 23 million) went to low-income countries between 2015 and 2020. And only one third of countries require safety inspections for used vehicles, a worrying figure in Africa, which has the largest market share of used vehicles and the highest mortality rate.

The 5% decrease is meagre compared to the target of -50% by 2030, yet the Global status report points the way: “Some of the greatest results have been achieved where an approach that puts people and safety at the centre of mobility systems has been widely applied,” the WHO concludes. “Ten countries managed to reduce deaths by half between 2010 and 2021, and these examples show that ambitious death reduction targets can be achieved, given the right level of political will and if the right measures are taken.”